Text Structure of Political Misinformation

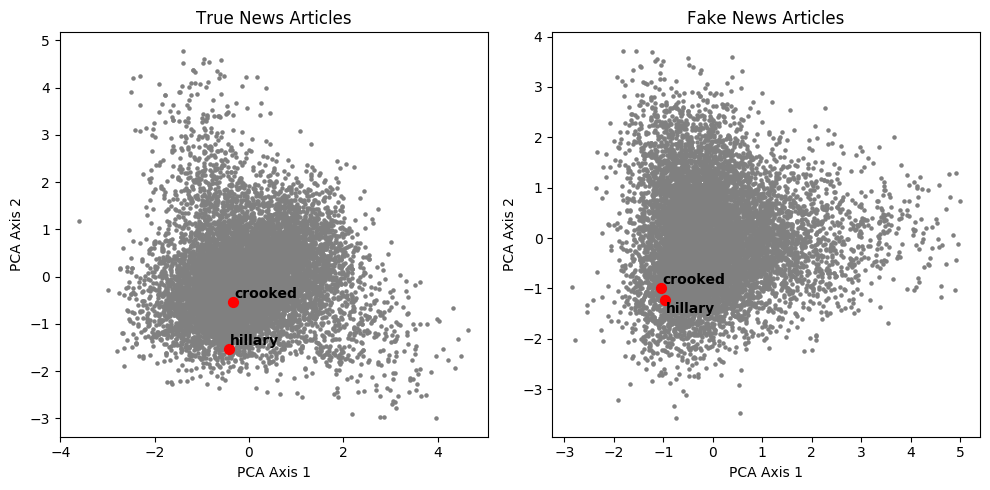

Word2Vec representations of real and fake News

The flagging of fake news has become a major issue for social networks and internet platforms. Though human moderators and crowdsourcing techniques are mostly employed to combat the spread of misinformation, the hope for some is that Natural Language Processing and AI will soon be capable of identifying fake news immediately, as Mark Zucherberg told the US Congress last year.

In this exploratory project, we take an existing dataset of real and fake news entries, and look at how they present different text structures, ie. if words are used differently in real news and in fake news. The data we use was compiled by George McIntire in 2017, and used by the author to build a Baysian classification model of fake news (the results for published on OpenDataScience.com).

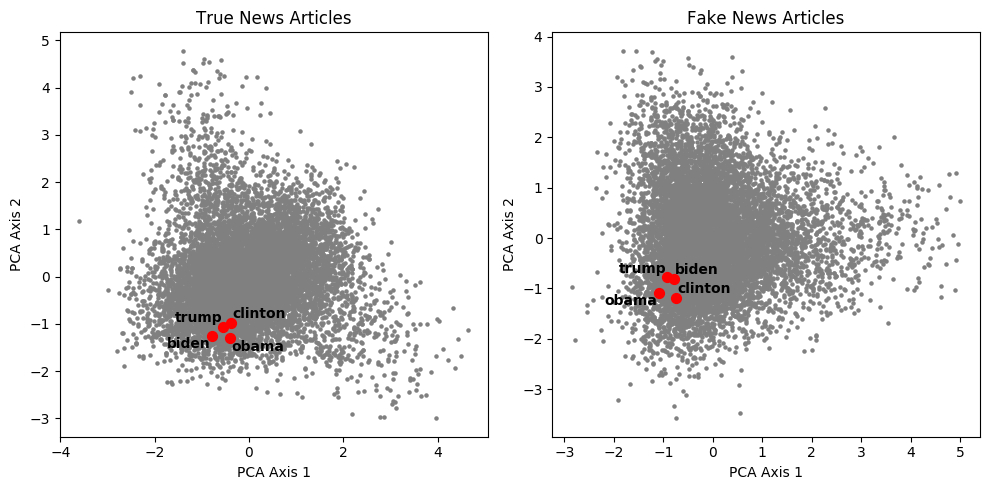

We use the word2vec sequence model to assign two high-dimensionality vectors to every word: one in the True News corpus and one among the Fake News entries. We then plot the words according to the two first principal components of the data, and observe the relative positions of the same words in both corpora. Our main findings are that, even though fake news does have some of the same structural logic as real news—and that most words have similar relative positions in both—, there are some important differences, especially on political or polarizing terms.

Data

The data we use was collected by George McIntire in 2017. The data and model used to be available on this GitHub repository, but it has appartently been pulled down recently. You can download the data as we used it here.

The corpus of real and fake news articles covers the 2015-2016 period of the most recent US presidential election cycle.

Modeling

The modeling method we use is word2vec, a common Natural Language Processing model that assigns a high-dimensionality vector to every word depending on sequential similarities with other words. Based on a words neighbors, word2vec will create a representation in which related terms have similar vectors. There are many existing online resources on word2vec: we recommend looking here for more information about the algorithm or here for the original paper by Mikolov et al.

We set a number of parameters for our model, which is available in this GitHub repository. The sliding window size is set to 4, meaning we consider the 8 nearest neighbors to every word to evaluate a word’s vector. The vocabulary is restricted to the top 10,000 words of the two corpora. The dimensionality of each word’s vector is set at 150. Finally, we run 10,000 iterations of gradient descent to obtain our final vector values.

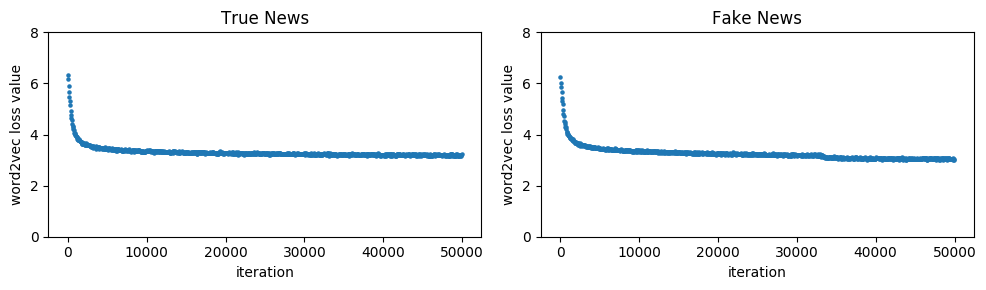

Our word2vec algorithm quickly converges for both True and Fake News. The values of the loss function at every iteration is presented below.

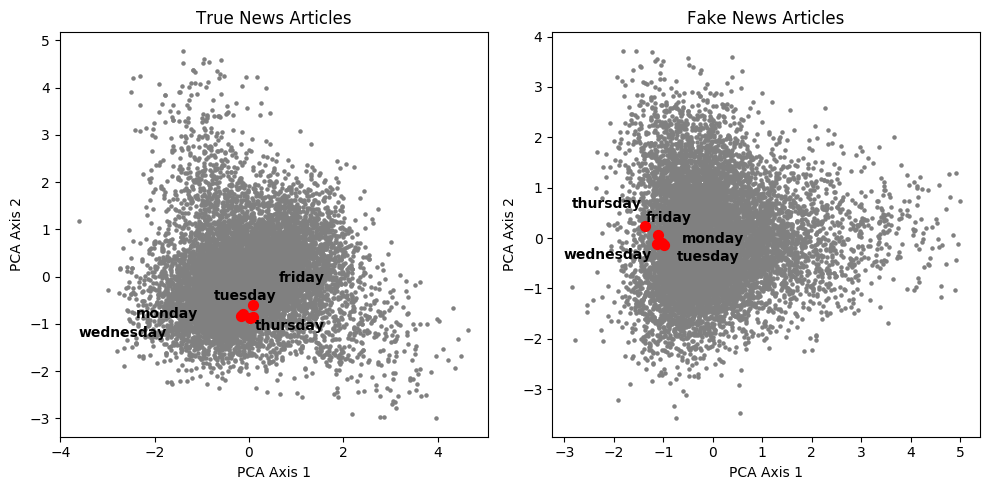

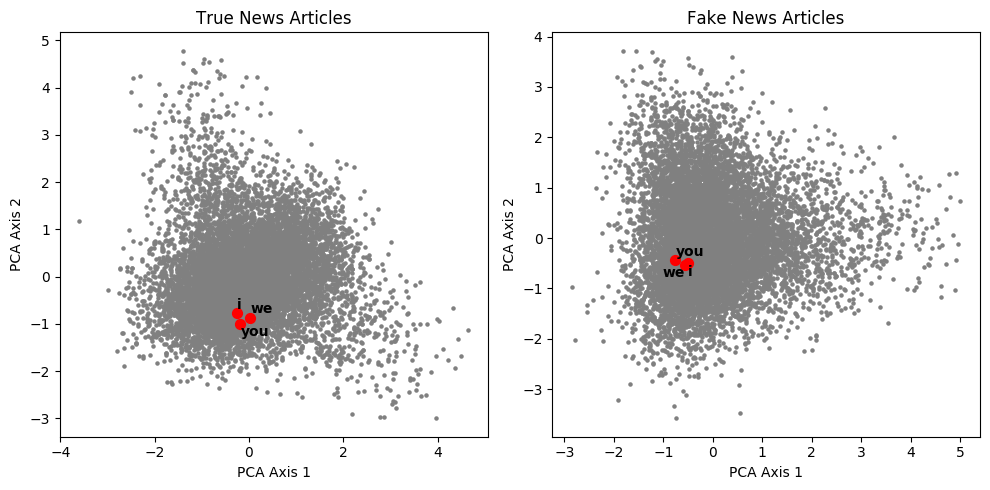

Once we compute each word’s 150-dimension vector, we can visualize relative word positions on a two-dimensional plot using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The scatters of words according to the two first components of the PCA are presented below.

Real and Fake News present similar overall structures

Overall, real and fake news present many similarities in their structures. Words that intuitively should present similar vectors, such as weekdays, pronouns, state names, or country names, appear tightly clustered in both the real and fake news topologies.

In addition to confirming the relevance of the word2vec representation, this proves that most fake news has the same overall textual structure, grammar, and syntax as real news. Fake news is not a non-sensical succession of random words: it is written in comprehensible English, usually by a real person. This is what makes classification between real and fake news so difficult, regardless of the text features used.

Personalities, such as Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and Barack Obama, also appear as very clustered in both real and fake news articles. While this is consistent with expectations, it makes it harder to associate specific words with any one of the politicians.

But some stark differences highlight the polarized nature of the media landscape

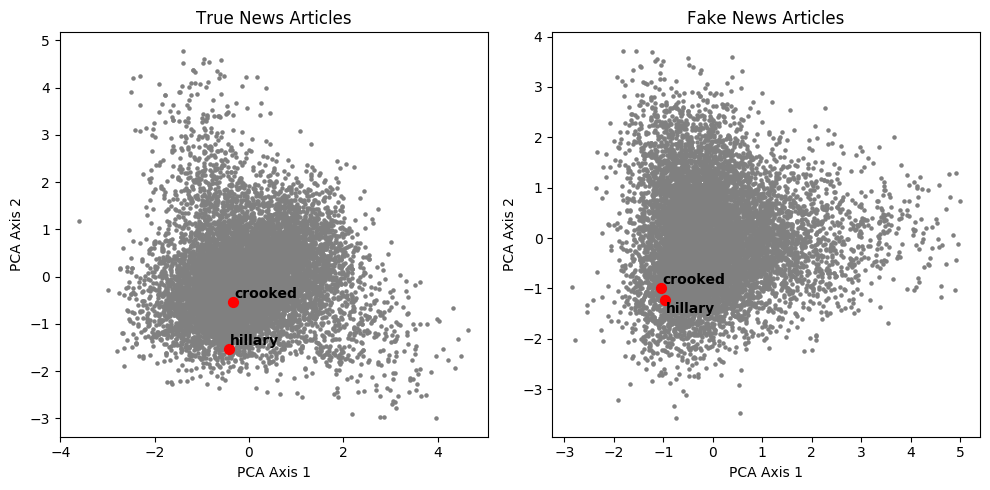

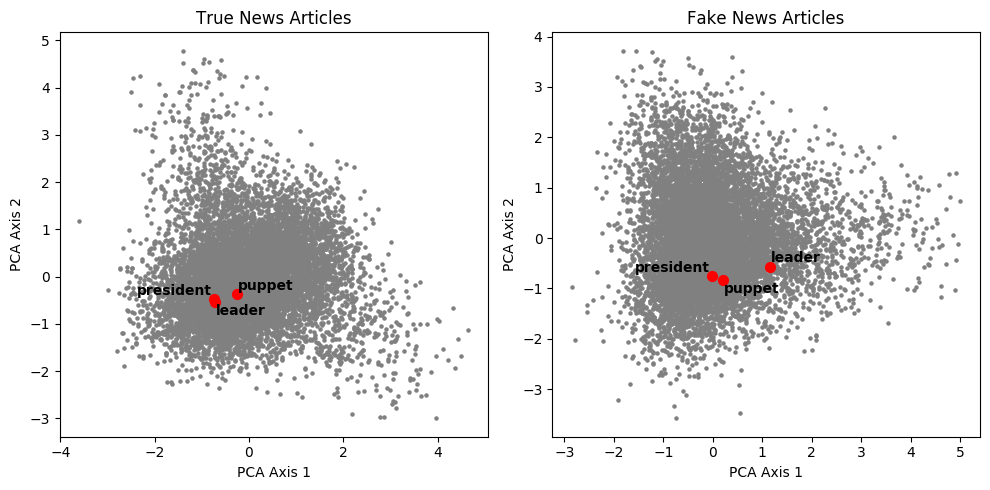

However, on a series of specific terms we tested, we notice that the structures of real and fake news differ. Most of these occurrences highlight polarizing political topics, usually surrounding the 2016 US presidential election.

The nickname “Crooked Hillary”, coined by Donald Trump in the runnup to 2016, was massively adopted by his supporters and by far-right conspiracy media. Here, we notice that the words “crooked” and “hillary”, logically distant in the real news representation, almost coincide in the fake news topology.

Another interesting difference regards characterizations of the word “president”. Words that would appear to be synonyms, such as “leader”, are very close in the traditional news representation. But in our corpus of Fake News, the word “president” appears closer to “puppet” than to “leader”! Given the articles collected by George McIntire cover a period between 2015 and 2016—the end of the Obama presidency and the 2016 election cycle—, the malignant coverage of Obama’s presidency seems to have been predominantly negative.

For more exploration…

In case you’re interested in doing any additional research, we have shared all the data and results on the project repo. Feel free to reuse and let us know if you find anything interesting!